Their world was four walls and their shaper zone” (14). The idea of a half-billion inhabitants strikes a late-twentieth-century reader as virtually incomprehensible and later, when an apartment is described as “a good kilometer in the air” (151) one wonders how a city, at least as we currently understand the phenomenon, can consist of such structures and such a population.ĭickinson slowly reveals other details of his futuristic city: “Most people stayed in their rooms all day, just to get away from one another.

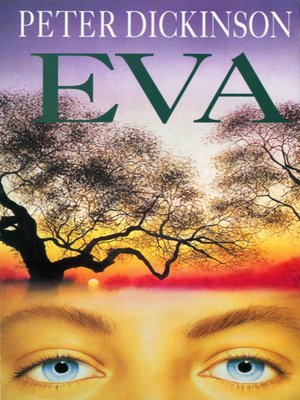

Later on, as the city’s half-billion inhabitants began to stir about the streets the mist would rise, thinning as it rose, becoming just a haze. She must be a long way up in a highrise herself, she could see so far. Highrise beyond highrise, far into the distance, all rising out of mist, the familiar, slightly brownish floating dawn mist that you always seemed to get in the city at the start of a fine day. Confined to her hospital bed after a horrific automobile accident, the symbolically named Eva Adamson can manipulate an overhead mirror to give herself a view from the hospital’s windows. One of the more disturbing images of the city springs to life in Peter Dickinson’s 1988 novel for young adults, Eva. They loom as frightening repositories of our intractable problems: crowding, crime, pollution, alienation, out-of-control technology, and human arrogance. When we examine novels set in the century yet to come, cities are hostile to all human life. Perusing the list of Carnegie Medal winners since the award’s inception in 1937 suggests that for the twentieth-century British sensibility, urban life and juvenile well-being are somehow essentially incompatible. If not nature, writers may endorse the “it takes a village” mentality and focus on the small community of a boarding school. Romantic considerations position children in nature, seldom portrayed as “red in tooth and claw” for young readers but more likely the enchanted rurality of a country house’s park or garden, as in Lucy Boston’s Green Knowe series. Fictive London children escape from their urban environment to cozy exurbs like the one that welcomes Oliver Twist or fantasy realms such as the Pevenseys’ Narnia or the Darlings’ Neverland. From the days of Dickens on, British fiction about or for children has seldom shown the city as a place where satisfactory childhoods can be experienced.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)